Trish Jones knew trouble was brewing when her right shoulder began to throb during her favorite yoga class. The 29-year-old was no stranger to such pain. She had suffered from unstable shoulder joints for years. Her doctors call it “multidirectional instability, ” but Jones refers to it as “having loose nuts and bolts.” So loose that in 1995 she had surgery to stabilize her left shoulder. Last summer, when pain began to gnaw at her other shoulder, she couldn’t shake the feeling that it was in trouble, too.

Still, Jones kept practicing Ashtanga three times a week at a studio near her home in Alexandria, Virginia, in hopes that the pain would work itself out. That is, until her right shoulder dislocated in Vasisthasana (Side Plank Pose). “Luckily, I knew exactly what happened, so I went out into the hall and popped it back in, ” she says. Still, the incident served as a wake-up call. She knew the way to dodge a second surgery was to figure out how yoga could build up her shoulder strength without aggravating the instability.

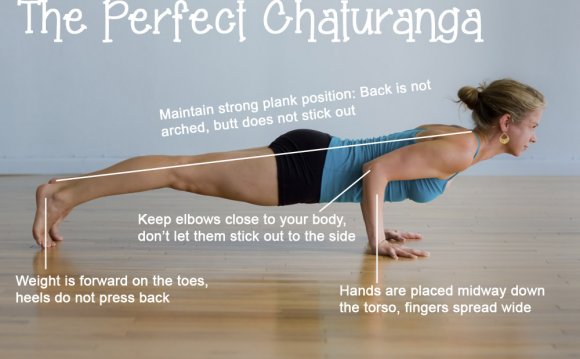

After her injury, Jones switched to a restorative yoga practice and sought advice from yoga teachers, physical therapists, and doctors. Two weeks later, she was back at the studio. Under the close supervision of her teacher, she modified every pose in the Ashtanga primary and second series to spare her shoulder. They jettisoned all weight-bearing asanas, like Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose) and Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose), and took an easy-does-it approach to shoulder openers, like Marichyasana I (Marichi’s Twist I.) “It was a much different practice than the typical first series, ” Jones says, “but it wasn’t in my best interest to stop practicing altogether.”

Although Jones was eager to build strength in the damaged joint, she knew the only way to thwart another dislocation was to perfect her alignment. So she analyzed her shoulder position in every pose. To prevent rounding forward in the front of the shoulders, she started each asana by widening her collarbones. To protect the back of the joints, she made sure her upper back was engaged, with the bottom tips of the shoulder blades drawing together and down. Soon, these shoulder adjustments became a meditation in themselves.

As Jones found out, yoga can be a boon to the shoulders, but it can also be a bust. While an intense yoga class can leave your shoulder muscles a little sore the next day, you shouldn’t steamroll past any sharp or throbbing pain in the joint during or after practice. If your shoulders start to gripe whenever you roll out your mat, it’s time to tune in and figure out what’s going on before you do more harm than good. If your shoulders are free of trouble, don’t be overconfident: Now is the time to protect them from future injury. Either way, your shoulders will thank you, and your yoga practice will be stronger.

How it Works

Shoulder problems shouldn’t be shrugged off. In 2003 (the latest year for which numbers are available), nearly 14 million Americans visited a doctor complaining of a bum shoulder. Joint instability, like Jones’s, is one of the most common ailments. Others include impingements, rotator cuff tears, and arthritis.

Athletes often suffer disproportionately from shoulder injuries because the various repetitive movements stress the joints, says Jeffrey Abrams, an orthopedic surgeon in Princeton, New Jersey, and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. “In other countries people play soccer, but here we like to ski and play golf and tennis, all of which are hard on the shoulders.” Jones is a typical example—when she was younger she played basketball and tennis and loved rock climbing. Now she puts her shoulders through their paces in Ashtanga.

But there’s another factor at play—the natural structure of the joint. “Shoulders are designed for mobility, not stability, ” says Roger Cole, Ph.D., an Iyengar-certified teacher in Del Mar, California, who teaches workshops on shoulder safety. The mobility allows for an astonishing range of motion compared to that in the hips—if you have healthy shoulders you can move your arms forward, back, across the body, and in 360-degree circles. But the relatively loose joint relies on a delicate web of soft tissue to hold it together, which makes it more vulnerable to injury. (The soft tissue includes ligaments, which connect bone to bone; tendons, which attach muscle to bone; and muscles, which move and stabilize the bones.)

The main ball-and-socket joint is also quite shallow, adding to the flexibility but putting the joint at risk. Abrams likens it to a basketball sitting on top of a plunger. (The basketball is the head of the humerus, or upper arm bone, and the plunger is where it meets the scapula.) The rotation of a big ball on a little base makes the shoulder mobile.